Introduction

physical activity is integral to overall health, reducing teh risks of chronic disease, enhancing psychological well-being, and improving functional capacity across the lifespan.However, the physiological stress of an intense workout-including microtrauma to muscle fibers, transient inflammation, and metabolic shifts-necessitates effective recovery to optimize adaptation and minimize injury risk [CDC], [WHO]. Evidence-based recovery strategies are essential for both amateur and elite athletes to promote tissue repair, restore performance capacity, and support holistic health.

Understanding Exercise-Induced Physiological Stress

Intense exercise initiates a cascade of physiological responses, including increased production of reactive oxygen species, metabolic by-product accumulation (e.g., lactate), and inflammatory mediators [NCBI]. These processes,while central to adaptive changes such as hypertrophy and enhanced aerobic capacity,also cause delayed-onset muscle soreness (DOMS),temporary performance decrements,and heightened risk of musculoskeletal injury if not adequately managed [Mayo Clinic].

The main objectives of recovery are to:

- Facilitate muscle and connective tissue repair

- Restore central and peripheral nervous system balance

- Replenish glycogen and fluid stores

- Modulate inflammation and oxidative stress

Appropriate recovery is thus fundamental to sustained athletic performance, injury prevention, and maintenance of the physiological adaptive process.

Key Evidence-Based recovery Techniques

1. Active Recovery

Active recovery refers to low- to moderate-intensity physical activity following strenuous exercise. scientific studies highlight its effectiveness in accelerating lactate clearance, attenuating muscle soreness, and facilitating neuromuscular function recovery [NCBI].

- Methods: Gentle cycling, swimming, yoga, brisk walking, and light calisthenics.

- Mechanisms: Enhances circulation, delivers oxygen and nutrients to tissues, and supports removal of metabolic by-products.

- Practical Advice: 10-30 minutes of active recovery at 40-60% of maximum effort after high-intensity activity.

2. Nutrition: Timing, Composition, and Hydration

Nutritional strategies -exercise significantly influence recovery outcomes. Attention to macronutrient composition and hydration status enhances muscle glycogen resynthesis and repair of muscle microdamage [Harvard Health].

- protein: Consumption of 20-40 g of high-quality protein within 30-60 minutes after exercise stimulates muscle protein synthesis and recovery [PubMed].

- Carbohydrates: 1.0-1.2 g/kg/h carbohydrate intake aids in rapid glycogen replacement, especially critically important for endurance athletes [NCBI].

- Fluids and Electrolytes: Replace 150% of fluid lost through sweat within 4-6 hours -exercise, using oral rehydration solutions especially when significant electrolyte loss is expected [NCBI].

- Micronutrients: Antioxidants (vitamins C & E), omega-3 fatty acids, and polyphenols may aid in reducing oxidative stress and inflammation, though excessive antioxidant supplementation may blunt beneficial adaptations [NCBI].

3.Sleep and Circadian Optimization

sleep is the most potent natural recovery tool. During slow-wave and REM sleep, anabolic hormonal secretion (growth hormone, testosterone) peaks, facilitating tissue repair, cognitive restoration, and immune function [NCBI].

- Duration: 7-9 hours/night as per CDC guidelines, with increased need after exceptionally hard training or competition.

- Quality: Emphasize regular bed/wake times, minimize blue light exposure prior to sleep, and create an surroundings conducive to restful sleep.

- Nap Strategies: Napping (30-90 minutes) can be effective in reducing subjective fatigue and improving subsequent performance [JAMA].

4. Cold-Water Immersion (CWI) and Contrast Therapy

Cold-water immersion and contrast water therapy (alternating hot and cold) are popular interventions for reducing -exercise soreness and inflammation.

- mechanism: CWI constricts blood vessels, decreasing inflammatory response, swelling, and perceived pain, while contrast therapy induces vasoconstriction and vasodilation to enhance circulation [NCBI].

- Evidence: Meta-analyses show that CWI (10-15°C for 10-15 minutes) modestly reduces muscle soreness and markers of muscle damage [The Lancet].

- Note: Frequent use may blunt adaptation during strength phases. Use strategically during high-frequency competition schedules or acute injuries.

5. Stretching and Mobility work

While static stretching is no longer universally recommended pre-exercise, -exercise stretching and mobility routines support muscle adaptability, joint range of motion, and subjective recovery [Mayo Clinic].

- Dynamic and static Stretching: Gentle stretches targeting major muscle groups held for 20-30 seconds -workout.

- Foam Rolling (Self-Myofascial Release): Improves soft tissue compliance, reduces perceived muscle soreness, and increases blood flow [NCBI].

- PNF Stretching: Proprioceptive Neuromuscular Facilitation may provide additional improvements in flexibility, though requires guidance for safe implementation.

6. Massage Therapy

Massage is extensively studied for its role in reducing muscle soreness, modulating inflammation, and promoting relaxation. Mechanistically, massage may improve lymphatic outflow, reduce muscle stiffness, and relieve psychological stress [NCBI].

- Sports Massage: Best applied within several hours -exercise for maximal effect on DOMS and subjective recovery.

- Self-Massage Tools: Balls and foam rollers can be effective alternatives or adjuncts.

- Evidence: Massage demonstrates moderate benefits for pain reduction and functional recovery -exercise [NCBI].

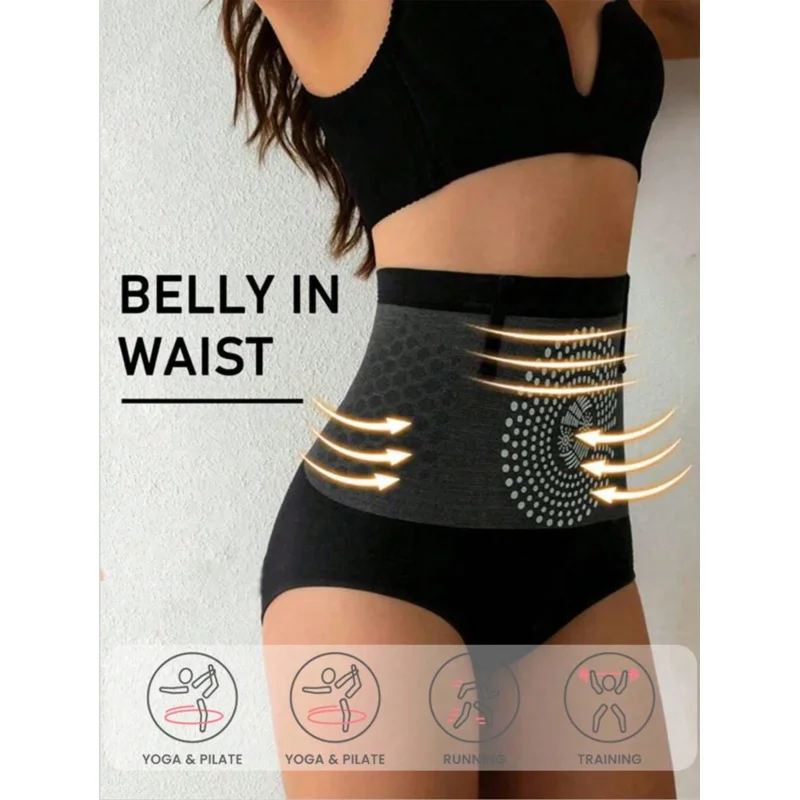

7. Compression Garments

Graduated compression garments are theorized to augment venous return, reduce edema, and improve muscle oxygenation following strenuous activity. Meta-analyses indicate small, but meaningful, effects on perceived soreness and recovery of power output in some populations [JAMA].

- Application: Worn immediately -exercise for several hours to overnight, depending on comfort and manufacturer instructions.

- Population: Especially beneficial during periods of heavy training load and for team-sport athletes experiencing frequent match play.

8. Other Modalities: Emerging and Adjunct Techniques

A variety of adjunct modalities have seen increasing interest,though their evidence base is presently more limited or mixed.

- Electrical Muscle Stimulation (EMS): May accelerate vascular and lymphatic flow but with mixed evidence regarding recovery benefits [NCBI].

- Percussive Therapy Devices: Early research suggests potential in reducing muscle soreness, but further study is needed for consensus [Medical News Today].

- Infrared Sauna: May support circulation and relaxation but awaits further large-scale validation.

Integrated Recovery planning: Practical Protocols and Individualization

The optimal recovery protocol is inherently individual, shaped by exercise type, load, the athlete’s age and health status, baseline fitness, and lifestyle constraints. An evidence-informed approach prioritizes core strategies-nutrition, hydration, sleep, and active recovery-alongside adjuncts as warranted by context and personal experience [NHS].

| Strategy | Timing | Key Actions |

|---|---|---|

| Active Recovery | Within 1-2 hours -exercise | 10-30 min low-intensity activity |

| Nutrition and Hydration | Within 30-60 min -exercise | 20-40g protein, 1-1.2g/kg carbs, rehydration |

| Sleep | Nightly/As needed | 7-9 hours quality sleep, napping |

| Mobility & Stretching | Immediately -exercise/daily | Gentle stretching, foam rolling |

| CWI & Contrast Therapy | Within hours -intensive sessions | 10-15 min at 10-15°C (CWI) |

| Massage, Compression, Adjuncts | As tolerated | Massage, compression wear |

Special Populations and Clinical Considerations

Recovery protocols must consider comorbidities, age-related changes, medication use, and unique risk profiles. For example, older adults experience slower tissue regeneration, necessitating additional focus on protein intake and joint-friendly recovery modalities [Harvard]. Those with cardiovascular disease or metabolic syndrome should avoid extreme cold therapy in favor of active and nutritional strategies [NHS].

Mistakes and Myths in exercise Recovery

- neglecting Hydration: dehydration impairs all facets of recovery, including cognitive function and muscle repair [CDC].

- Overuse of NSAIDs: Frequent nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug use may mask injury and blunt healing responses; employ judiciously under medical guidance [FDA].

- Reliance on Supplements: While some supplements help, most recovery should come from whole foods and evidence-based practices [NIH].

- Ignoring Mental Health: Psychological stress impairs physical recovery. Cognitive behavioral strategies and mindfulness should be considered part of the holistic recovery process [Mayo Clinic].

Actionable Tips for Maximizing Recovery

- Prioritize consistent sleep and sleep hygiene.

- Individualize recovery based on exercise modality, fatigue, and personal response.

- Monitor biomarkers (subjective well-being, heart rate variability, soreness) to guide recovery interventions.

- Communicate with healthcare professionals for recurring or severe pain, fatigue, or injury signs.

Conclusion

Effective recovery after intense workouts is grounded in sound physiology and clinical evidence. through a multifaceted approach-combining active recovery, precision nutrition, restorative sleep, hydration, and, where appropriate, adjunct therapies-athletes and recreational exercisers alike can optimize adaptation, mitigate injury risk, and sustain lifelong health and performance.Adhering to these science-based strategies,personalized to individual needs and medical backgrounds,provides a robust foundation for safe,sustainable fitness progress.

References

- CDC – Physical activity and Health

- WHO – physical Activity

- Mayo Clinic – sore muscles after exercise

- Harvard Health – recovery after a workout

- NCBI – Nutrition and recovery

- NCBI – Cold-water immersion effectiveness

- Mayo Clinic – Stretching: Understand the basics

- JAMA – Compression garment recovery

- Harvard Health – Exercise and aging

- FDA – Safety of pain relievers

- NHS – Exercise health benefits

- Mayo Clinic – Stress management

- NCBI – Massage effectiveness

- NCBI – Fluid and electrolyte replacement

- pubmed – Protein for muscle recovery