<img class="vimage_class" src="https://healthblog.s3.eu-north-1.amazonaws.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/11/23163603/98685.jpeg" alt="back pain exercises”>

Introduction

Back pain is a leading cause of disability globally, affecting millions of people across all age groups. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), low back pain alone is the single greatest cause of disability worldwide. Equally, poor ure is pervasive in modern society, exacerbated by increasingly sedentary lifestyles and extensive use of computers and mobile devices. The clinical and economic burden of chronic back pain and ural dysfunction is immense, affecting not only individual health and well-being but also productivity and healthcare systems.

Emerging evidence highlights that carefully structured exercise regimens can substantially reduce back pain, enhance musculoskeletal function, and correct ural imbalances.In addition, therapeutic exercise represents a core component of both primary prevention and management protocols for non-specific back pain as per guidelines from leading health authorities like the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). This evidence-based, in-depth article explores the most effective exercises for reducing back pain and improving ure, synthesizing insights from peer-reviewed research and clinical sources.

Understanding Back Pain: epidemiology, Pathophysiology, and Risk Factors

Epidemiology and Public Health Importance

Globally, it is indeed estimated that up to 840 million people will experience back pain in their lifetime. Most adults will encounter some form of back pain by age 60. The burden is not merely physical; back pain significantly impacts mental health, leading to anxiety, depression, and impaired quality of life (NCBI).

Etiology and Pathophysiology

The majority of back pain cases are classified as “non-specific,” meaning no specific anatomical cause can be found (Mayo Clinic). Common pathophysiological factors include:

- Muscle or ligament strain due to improper lifting or sudden awkward movements

- Prolonged poor ure leading to muscle imbalance and joint dysfunction

- Degenerative changes (e.g., osteoarthritis, intervertebral disc degeneration)

- Structural problems (e.g., herniated discs, spinal stenosis)

Modifiable Risk Factors

Several modifiable risk factors increase susceptibility to back pain and poor ure, including:

- Physical inactivity or sedentary behavior

- Obesity and metabolic syndrome

- Poor ergonomics at work and home

- Muscle weakness or imbalance

- Inadequate core stability

Addressing these through focused exercise programming can be profoundly protective and therapeutic.

The Importance of Exercise in Back Pain Management and ure Correction

Clinical Guidelines and Systematic Reviews

Major clinical practise guidelines-including those from the American College of Physicians (ACP)-consistently advocate for structured physical activity and targeted exercise as first-line interventions for chronic low back pain and ural syndromes. Evidence from NHS and CDC suggests that individualized exercise therapy improves pain scores,enhances function,and reduces recurrence rates.

Therapeutic Mechanisms

Exercise yields multiple therapeutic benefits for the spine and ural musculature (Harvard Health), including:

- Muscle strengthening: Builds resilience of the spinal stabilizers and ural support muscles

- Versatility advancement: Reduces rigidity and allows more efficient movement

- enhanced neuromuscular control: Optimizes movement patterns and ure alignment

- Reduction of inflammation: Promotes circulation and healing in affected tissues

- Prevention of future injuries: Reduces risk of recurrence and progression

Why Passive Approaches alone Are Not Sufficient

Unlike medication, rest, or passive modalities (e.g., electrical stimulation, massage), exercise directly addresses the underlying biomechanical contributors to dysfunction (medicinenet), making it essential for effective long-term management.

Key Exercise principles for Back Pain and ure Improvement

Evidence-Based Approach to Exercise Prescription

Exercise programs should always be tailored to the individual’s diagnosis, fitness level, and goals. The following principles are generally supported by published clinical studies and public health recommendations:

- Frequency: Aim for a minimum of 2-3 dedicated sessions per week

- Intensity: Start with low to moderate intensity; progress gradually as tolerated

- Type: Incorporate a balanced mix of strengthening, stretching, and motor control exercises

- Progression: Increase the difficulty or complexity every 2-4 weeks based on individual response

- Supervision: Seek professional guidance for proper technique, especially in early stages or for complex cases

Precautions and Contraindications

not all exercises are appropriate for everyone. certain conditions-such as acute fractures, malignancy, or infections-may require medical clearance before starting any program (Mayo Clinic).If symptoms worsen during activity, discontinue and consult a healthcare provider.

Comprehensive Exercise Categories for Back Pain and ure

Therapeutic exercise for spinal health can be organized into several core categories:

- Core Stability and Strengthening

- Flexibility and stretching

- ural Correction and Motor Control

- aerobic Conditioning

- Functional and Balance Training

Below, we detail the most effective exercises within each domain, cited by leading clinical research and expert consensus.

Core Stability and Strengthening Exercises

Scientific Rationale

The lumbar spine depends on a well-coordinated “core” of muscles-including the rectus abdominis, transverse abdominis, multifidus, pelvic floor, and diaphragm-for stability and protection against excessive load (NCBI). Weak or uncoordinated core musculature is a key risk factor for chronic low back pain and ural collapse.

Top Core Exercises Supported by Evidence

-

Abdominal Drawing-In Maneuver (ADIM)

How it works: This foundational exercise activates the deep abdominal stabilizers without over-recruiting superficial muscles.

- Lie on your back, knees bent, feet flat.

- Gently pull your navel towards your spine without moving your pelvis or rib cage.

- Hold for 10 seconds; repeat 10-15 times.

ADIM is strongly endorsed by research for both acute and chronic non-specific low back pain (NCBI).

-

Bird-Dog

Purpose: Enhances spinal stability and proprioception.

- start on hands and knees, spine neutral.

- Together extend the right arm and left leg, keeping hips level.

- Hold 5-10 seconds; alternate sides; 10 repetitions each.

Widely used in physical therapy; shown to reduce pain and correct abnormal movement patterns (harvard Health).

-

Side Plank

Targets: Lateral core muscles (obliques, quadratus lumborum) essential for ure and load-sharing.

- Lie on your side, elbow directly under shoulder.

- Lift hips to align spine; hold for 10-30 seconds.

- Repeat 3-5 times; switch sides.

Clinical trials highlight side plank’s benefits in reducing recurrence of lower back pain (Medical News Today).

-

Pelvic Tilt / Bridge

Purpose: Strengthens gluteal and lower back muscles while promoting pelvic alignment.

- Lie on back, feet flat and hip-width apart.

- Press lower back into floor, then lift pelvis towards ceiling.

- Hold 5-10 seconds; repeat 10-15 times.

Flexibility and Stretching Exercises

Why Flexibility Matters

Muscle tightness-particularly in the hamstrings, hip flexors, and lumbar paraspinals-can overload the spine and worsen ural mechanics (NCBI).Regular stretching alleviates tension, increases joint mobility, and enables optimal movement patterns.

key Stretches for Spinal Health

-

Knee-to-Chest Stretch

- Lie on back, draw one knee toward chest.

- hold 20-30 seconds; repeat 2-3 times per side.

-

Child’s pose (Yoga)

- Kneel, sit back on heels, reach arms forward on floor.

- hold 30-60 seconds.

Frequently used in yoga for gentle lumbar decompression (Healthline).

-

Cat-Cow Stretch

- On all fours, alternate arching (cat) and dipping (cow) the spine.

- Cycle slowly 10-15 times to mobilize vertebrae.

-

Hamstring Stretch

- Sit with one leg extended, the other bent.

- Lean slowly forward from hips toward toes.

- Hold for 20-30 seconds each leg.

Hamstring flexibility is highly correlated with pain intensity and likelihood of recurrence (NCBI).

ural Correction and Motor Control Exercises

Role of ural Training

Poor ural habits-such as slumped sitting and rounded shoulders-disrupt spinal alignment and overload the musculoskeletal system (medlineplus). Motor control retraining “re-educates” muscles and joints to maintain ideal positioning during daily activities.

Recommended Exercises

-

Wall Angels

- Stand with back and head flat against a wall, arms raised.

- Slide arms slowly up and down, maintaining wall contact.

- Repeat for 10-15 repetitions.

Improves thoracic extension and scapular movement, crucial for upper and lower back ure (Harvard Health).

-

Chin Tucks

- Sit or stand upright, gently pull chin toward neck (creating a “double chin”).

- Hold for 5-10 seconds; repeat 10-15 times.

Facilitates alignment of cervical spine for optimal ure (Healthline).

-

Seated ure Hold

- Sit tall, engage core, shoulders back and down.

- Hold this ideal position for 1-2 minutes, repeat frequently throughout the day.

Regular “ure resets” integrate neuromuscular control into everyday life (Mayo Clinic).

Aerobic and Functional Conditioning

Why Cardiovascular Fitness Matters

While not specific to the back, general aerobic exercise (e.g., walking, cycling, swimming) improves microcirculation, reduces inflammation, and enhances pain inhibition via endogenous endorphin production (NCBI).

Safe Aerobic Options

- Walking: Preferred starting point for most, with minimal spinal load

- Swimming / Water Aerobics: Provides buoyancy and pain relief for severe cases

- Stationary Cycling: Can be beneficial with proper ure

Functional Training

Functional movements (e.g., squats, lunges) improve total body integration and reduce strain on the spine during activities of daily living (medlineplus).

Balance and Proprioceptive Exercises

reducing Fall Risk and Enhancing Spinal Control

Instability and impaired proprioception exacerbate back pain and ural deficits (NCBI). Balance training activates deep spinal stabilizers and corrects asymmetries.

Examples

- Single-leg Stance: Stand on one leg for 20-30 seconds; challenge by closing eyes or standing on a soft surface

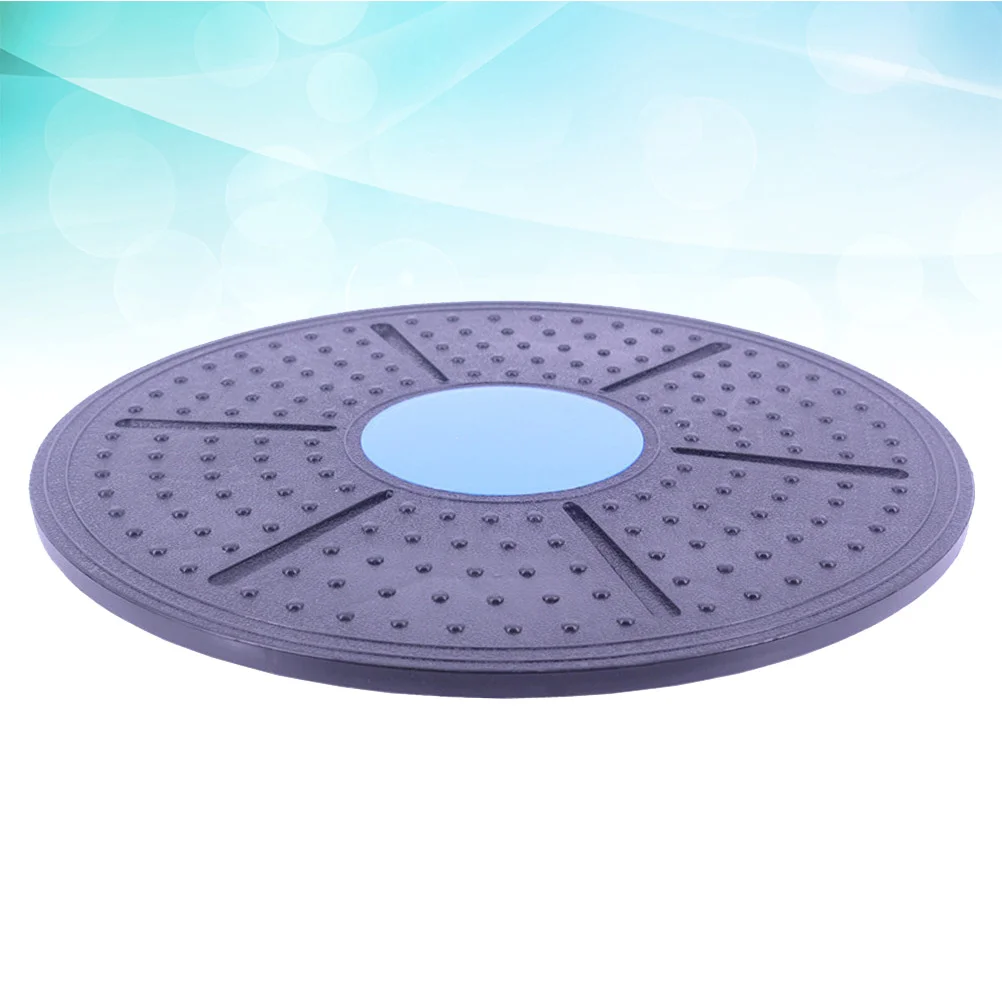

- Balance Board / Stability Cushion: Perform gentle squats, weight shifts, or core holds on an unstable surface

Regular integration of balance exercises can lower pain and injury rates in at-risk populations.

Yoga and Pilates for Back Pain and ure

Evidence-Based Benefits

Both yoga and Pilates are supported by randomized controlled trials as safe, accessible modalities for chronic back pain and ural correction. These practices combine stretching, strengthening, and conscious movement, fostering body awareness and neuromuscular control.

Key Poses and Moves

- Cobra Pose (Bhujangasana): Promotes lumbar extension; hold for 15-30 seconds

- Plank Variations: Strengthen anterior and erior chains

- pilates “Hundred” and Roll-Ups: Build core engagement and controlled spinal movement

Group classes or guided sessions with certified instructors are advised for correct technique and individualized adaptation.

Ergonomics and daily Lifestyle Strategies

Integrating Exercise into Daily Routines

Research consistently demonstrates that “micro-breaks” and ure resets-performed every 30-60 minutes-dramatically reduce discomfort, preserve spinal alignment, and offset cumulative stress (Harvard Health).

Workstation ergonomics

- Monitor Height: Top of screen at or just below eye level

- Chair Support: Lumbar roll or support cushion

- Frequent Moving: Stand, stretch, and walk each hour

Adapting your environment in tandem with exercise maximizes ural gains and reduces re-injury risk (CDC Ergonomics).

sample Back Pain relief and ure Care Routine

Beginner Routine (15-20 Minutes)

| Exercise | Duration / Reps | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Knee-to-Chest | 2 x 30 sec per side | flexibility,decompression |

| Cat-Cow | 2 x 10 cycles | Mobility |

| bird-Dog | 2 x 10 reps per side | Stability,balance |

| Side Plank | 2 x 15 sec per side | Core and obliques |

| Wall Angel | 2 x 10 reps | ure correction |

Progression and Frequency

Perform this sequence 3-4 times weekly. Gradually increase duration and repetitions as comfort and control improve. For persistent or severe pain, always consult with a physical therapist or healthcare provider.

Safety, Red Flags, and When to Seek Medical Advice

Warning Signs

Back pain that radiates into the legs, is accompanied by numbness, weakness, fever, or bowel/bladder changes may indicate serious pathology (e.g., nerve root compression, infection) and warrants immediate medical attention (NHS).

Professional Supervision

Exercise programs should be overseen by licensed professionals-such as physical therapists or physicians-if:

- Back pain is severe or worsening

- There is a history of spinal surgery or significant injury

- comorbid conditions (e.g., osteoporosis, neurological disease) are present

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Can exercise really replace medication or surgery for back pain?

For most cases of non-specific, mechanical back pain, exercise-based rehabilitation is the foundation of care and frequently obviates the need for chronic medication or surgical intervention (CDC). However, there are indications-such as severe structural disease-where additional interventions may be warranted. Always consult a clinician for personalized advice.

How long until I notice improvement?

Symptom reduction is typically observed within 4-8 weeks of regular, properly targeted exercise, but persistence and consistency are crucial (Harvard Health).

Are there activities to avoid?

High-impact sports, deep back bends, or heavy lifting should be avoided until pain is controlled and technique is mastered (Medical News Today).

Conclusion

Back pain and ural dysfunction are complex, multifactorial conditions with extensive impact on quality of life and societal productivity. Clinical evidence overwhelmingly supports deeply integrated, individualized exercise protocols-including strengthening, stretching, motor control, balance, and aerobic training-as the cornerstone of primary and secondary prevention efforts. By following structured, scientifically validated exercise guidelines and making ergonomic adjustments to daily environments, individuals can achieve significant, sustained improvements in spinal health, pain reduction, and ural alignment. When in doubt, collaboration with licensed healthcare professionals ensures safety and optimal outcomes. Begin your evidence-driven journey toward a stronger, pain-free back today.

References

- WHO: Low back pain fact sheet

- The Lancet: Global Burden of Low Back Pain

- NCBI: Management of Chronic Low Back Pain

- CDC: Physical Activity Basics

- NICE Guideline: Low Back Pain and Sciatica

- Harvard Health: Exercise for Back Pain

- Mayo Clinic: Back Pain Causes

- NHS: Back Pain treatment