Lower back pain that comes and goes without injury

Introduction

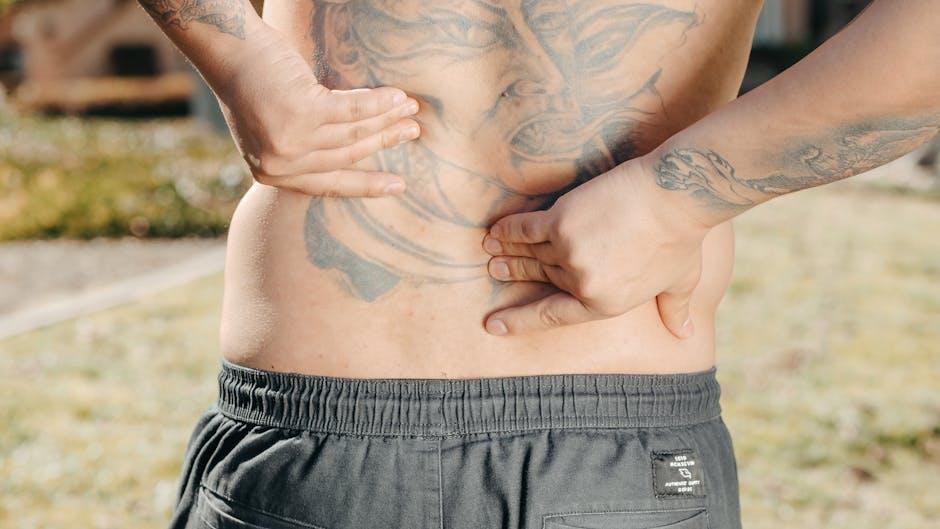

Lower back pain that comes and goes without a history of acute injury is a common but frequently misunderstood symptom that affects individuals worldwide. according too the World Health Institution (WHO), low back pain is the single leading cause of disability globally, impacting nearly 619 million people as of 2020. Persistent or intermittent pain in the lower back can disrupt everyday activities, contribute to work absenteeism, and reduce quality of life. While many associate back pain with injuries or trauma, a substantial proportion of sufferers report lower back pain that appears and subsides with no clear physical incident or precipitating event. This article examines the science, risk factors, clinical assessment, and evidence-based management options for lower back pain that comes and goes without injury.

Overview and Definition

Lower back pain, also known as lumbago, refers to discomfort or pain localized to the area between the lower rib cage and the gluteal folds of the buttocks. When present without identifiable structural injury (such as fracture,disc herniation,or major muscle strain),this pain is frequently enough termed “non-specific low back pain” or “mechanical low back pain.”

Clinically, intermittent lower back pain is characterized by episodes that resolve spontaneously, may recur periodically, and are not associated with acute trauma. The National Institutes of Health (NIH) notes that up to 90% of individuals with low back pain have a non-specific etiology, meaning that no precise anatomical cause can be steadfast, notably in the absence of overt injury.

Lower back pain commonly affects adults between the ages of 30 and 60, yet it can arise in younger and older populations as well. Studies show that nearly 80% of people will experiance some form of back pain in their lifetime, and for many, symptoms are recurrent and fluctuate over months or years (PubMed). The lumbar spine, comprising five vertebrae, intervertebral discs, ligaments, and various muscles and nerves, is the focal point of both pain sensation and functional mobility.

Causes and Risk Factors

The origins of lower back pain that comes and goes without an injury are multifactorial, involving both intrinsic and extrinsic contributors. In most individuals, the cause is not due to serious underlying disease but rather to functional or lifestyle factors that intermittently stress the tissues of the lumbar region.

Common Non-injury-Related Causes

- muscle Strain and Ligament Sprain: Repetitive minor stresses,poor ure,or deconditioning can lead to microtrauma and inflammation in lumbar musculature and supporting ligaments,even in the absence of a recognized injury (Mayo Clinic).

- Intervertebral Disc Degeneration: Age-related breakdown of the discs can trigger intermittent pain due to reduced shock absorption, though not always associated with a discrete injury (Harvard Health).

- Facet Joint Dysfunction: Wear and tear or inflammation in the small joints between vertebrae (zygapophyseal joints) can cause episodic pain,exacerbated by certain movements (pubmed).

- Muscle Imbalance and Weakness: Poor core muscle strength, tight hip flexors, or weak gluteal muscles frequently enough contribute to mechanical strain, frequently leading to pain that comes and goes with certain activities or prolonged sitting (Healthline).

Risk Factors and Underlying Mechanisms

- Sedentary Lifestyle: Prolonged sitting, common among desk workers and frequent drivers, places sustained pressure on spinal structures, which may increase the risk of episodic lower back pain (PubMed).

- Poor Ergonomics: Inadequate chair support,improper lifting techniques,or unsuitable workspace setups can cause chronic mechanical loading of the lumbar spine (OSHA).

- Obesity and Overweight: Excess body weight increases the mechanical burden on the lumbar vertebrae, predisposing to intermittent pain (CDC).

- Poor Physical Conditioning: Weakness or inflexibility in the abdomen, back, or hips puts individuals at greater risk of recurrent non-injury back pain (Harvard Health).

- Psychosocial Stress: Psychological factors such as depression, anxiety, or job dissatisfaction substantially correlate with the onset and persistence of non-injury low back pain (PubMed).

- Genetic Predisposition: Certain genetic markers may increase susceptibility to disc degeneration and chronic back pain (PubMed).

Pathophysiology: Why Does the Pain Come and Go?

The intermittent nature of lower back pain is often rooted in subtle physiological changes within the lumbar tissues rather than structural damage. Key mechanisms include:

- Fluctuating Inflammation: Low-grade,cyclical inflammation in muscles,ligaments,or facet joints can produce pain during flare-ups,which afterward resolves as the inflammation diminishes (Medical News Today).

- Nociceptive Sensitization: Increases in the sensitivity of pain receptors in lumbar tissues may cause pain to appear in response to mildly provocative stimuli (such as prolonged standing or bending), then abate during periods of rest (Nature).

- Central Pain Modulation: The central nervous system may intermittently amplify pain perception based on stress levels, fatigue, or concurrent psychological conditions (JAMA Psychiatry).

- Dynamic Biomechanical Loading: Variations in physical activity, ure, or weight-bearing load can transiently exacerbate pain, which resolves when biomechanical stress is alleviated (PubMed).

These factors frequently enough interact, producing the characteristic “comes and goes” pattern in many individuals with lower back pain not attributed to acute injury.

Clinical Presentation and symptomatology

Intermittent non-injury-related lower back pain typically presents as:

- Dull, aching, or throbbing pain in the lumbar area

- Occasional sharp or burning sensations, especially with specific movements

- Onset upon waking, after standing for long periods, or following mild exercise

- Resolution with changes in ure, rest, or basic stretching

- Absence of associated trauma, falls, or specific incident

In most cases, pain episodes last from a few hours to several days before subsiding, with symptom-free intervals in between. Occasionally, pain may radiate to the buttocks or upper thighs but without neurological deficits, such as weakness, numbness, or changes in bowel or bladder control (Mayo Clinic).

Warning signs that warrant urgent medical evaluation include unrelenting pain, fever, unexplained weight loss, history of cancer, important trauma, or neurological symptoms, as these may indicate a more serious, underlying condition (NHS).

Diagnostic Approach

most cases of lower back pain that comes and goes without injury are diagnosed based on a detailed clinical history and physical examination.

Key Components in Evaluation

- Medical History: Assessing the pattern, duration, severity, and provoking or relieving factors of the pain.

- Physical Examination: Inspection and palpation of the lumbar region, assessment of spinal mobility, muscle strength, and signs of nerve involvement.

- Red Flag Screening: Identification of alarm symptoms or past features suggestive of fracture, malignancy, infection, or cauda equina syndrome (CDC).

The Role of Imaging and Laboratory Testing

routine imaging studies (X-rays, MRI, or CT) and laboratory tests are not recommended in the initial workup for uncomplicated, non-injury lower back pain unless red flags are present (NICE). Indications for further investigation include:

- persistent pain beyond 6 weeks

- Progressive neurological symptoms

- Suspected underlying malignancy or infection

- Osteoporotic risk factors with suspicion for fracture

Diagnostic tests may include lumbar MRI (for suspected disc, nerve, or spinal cord pathology), blood tests (for infections or inflammatory disease), or bone scans when clinically indicated (Mayo Clinic).

Management and Treatment Strategies

The primary goal in treating lower back pain that comes and goes without injury is to relieve symptoms, restore functional mobility, and prevent recurrences with safe, evidence-based interventions.

Self-Management and Lifestyle Modifications

- Physical activity: Gradually increasing daily activity is recommended. Prolonged rest is not advised except for acute flare-ups. Walking, yoga, Pilates, or aquatic therapy can improve symptoms (Harvard Health).

- Exercise Therapy: Prescribed stretching, strengthening of core and lumbar muscles, and aerobic conditioning have proven benefits in reducing recurrence (PubMed).

- ural training: Correction of ergonomic risk factors at work and home (chair height, desk position, mattress firmness) reduces strain on the lower back (mayo Clinic).

- Weight Reduction: Achieving a healthy body weight lessens lumbar load (CDC).

- Smoking Cessation: Tobacco use impairs blood flow to spinal tissues and is a recognized risk factor for chronic pain (NIH).

Medication and Pharmacological Management

- non-prescription Analgesics: Acetaminophen and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), such as ibuprofen, can provide short-term relief during acute exacerbations (Mayo Clinic).

- Topical Analgesics: Lidocaine patches or NSAID gels may alleviate localized symptoms (Healthline).

- Prescription Medications: Short courses of muscle relaxants or, rarely, neuropathic agents (such as duloxetine) may be considered for select patients under physician supervision (PubMed).

Opioid medications are not recommended for non-specific, intermittent lower back pain due to risks of dependence and lack of proven long-term benefit (JAMA).

Physical Therapy and Option Modalities

- Manual Therapy: Physiotherapist-guided mobilization, massage, or manipulation may reduce pain intensity in the short term (PubMed).

- Cognitive Behavioral therapy (CBT): For individuals with significant psychosocial stress or maladaptive pain beliefs, CBT can definately help break the pain cycle and improve coping (pubmed).

- Acupuncture and Mind-Body Therapies: Select alternative therapies, including acupuncture and mindfulness-based stress reduction, have demonstrated modest benefits for some patients (Mayo Clinic).

Interventional and surgical Options

For persistent or functionally limiting pain (despite optimal conservative therapy and in the absence of structural injury), invasive interventions are rarely indicated. Examples include:

- Epidural steroid injections or radiofrequency ablation (for facet-mediated pain, only when noninvasive treatments fail)

- Surgical evaluation (reserved strictly for rare cases where undiagnosed pathology is found on imaging, or severe, refractory pain is present)

As a general rule, surgery is not required nor effective for most cases of intermittent, non-injury-related lower back pain (NHS).

Prevention: Reducing Recurrence and Long-Term Impact

- Regular Exercise: Engage in low-impact aerobic activities, stretching, and core strengthening at least 3–5 times per week (CDC).

- Ergonomic Adjustments: Use chairs with lumbar support, maintain good ure, and avoid improper lifting techniques (Harvard Health).

- Healthy Weight: Strive for a body mass index (BMI) in the normal range to lower lumbar stress.

- Stress Management: Addressing psychological stress, sleep disturbances, and work dissatisfaction can lessen susceptibility to recurrent pain (PubMed).

Prognosis and Long-Term Outlook

The prognosis for lower back pain that comes and goes without injury is generally favorable. Most individuals recover completely or experience manageable symptoms with appropriate modifications in lifestyle and physical activity. However, recurrence is common—up to 70% of individuals with low back pain experience a relapse within a year (The Lancet).

Only a small minority develop persistent, disabling pain or require advanced interventions. False beliefs about pain, excessive fear of movement, and failure to adopt healthy habits increase the risk of chronicity and disability. Early intervention and evidence-based education about the benign nature of most intermittent low back pain can improve outcomes and quality of life (MedlinePlus).

Frequently asked Questions (FAQ)

| Is lower back pain that comes and goes serious? | Most cases are benign and self-limited, but see a doctor if you develop neurological symptoms, fever, unintentional weight loss, or unremitting pain (Mayo Clinic). |

| Should I get an MRI or X-ray? | No, not unless there are red flag symptoms or persistent pain unresponsive to conservative therapy (NICE). |

| What lifestyle changes can reduce recurrence? | Increase physical activity, maintain a healthy weight, practise good ure, optimize your work habitat, and avoid tobacco use (Harvard Health). |

| When should I seek urgent care? | If you have loss of bladder/bowel control, leg weakness, numbness in the saddle area, high fever, or history of cancer, seek emergency evaluation (PubMed). |

Evidence-Based Resources and Further Reading

- Mayo Clinic – Symptoms and Causes of Back Pain

- CDC – Back Pain

- NHS – Back Pain Overview

- Harvard Health – Lower Back Pain A-to-Z Guide

- NIH – Non-specific low back pain: pathogenesis and Clinical Course

Conclusion

Lower back pain that comes and goes without injury is a widespread health issue with a generally favorable prognosis when managed with up-to-date, evidence-based strategies. Encouraging ongoing physical activity, correcting modifiable risk factors, and providing education about the typically benign course of intermittent non-injury back pain are vital for both acute relief and long-term prevention. Patients should seek medical attention for severe or persistent pain,or if any red flag symptoms develop. Through awareness and informed self-care, most individuals can maintain a pain-free and active life.